In 1896, as suddenly and unexpectedly as his meeting Douglas Blackburn and being spotted by Frank Podmore of the Society for Psychical Research had altered his life 14 years prior, George Albert Smith underwent another life-changing event: he went to the Empire Theatre in Leicester Square, which was exhibiting the first commercial theatrical showings of a projected film in the UK—a program exhibition by the Lumiere Brothers (British Pathe, 2022).

That same year, Smith bought his first film camera from Brighton-based engineer, Alfred Darling, who specialized in producing cinematographic equipment (Barnes, 2022). According to film editor and professor, Don Fairservice, Smith also built his own film camera during this same year (Fairservice, 2001). By the next year, in 1897, he began the process of turning a portion of his leased property into a film studio, repurposing part of the Pump House for a laboratory. In May of 1897, an article in the Hove Echo reported regarding the subject of “animated photographs”: “[Mr.] Smith was discovered near his laboratory, and on learning his visitor’s errand, immediately asked him into that mysterious chamber. A glance around the apartment was quite sufficient to impress one with the fact that the various appliances were there for practical use and not for show. The mechanical contrivances, baths containing [solutions, etc.,] all served to impress the uninitiated with a certain awe inseparable from that which is not understood” (Middleton J. , 2015).

G. A. Smith's studio in St. Ann's Well Gardens, set up for the brief rooftop scene toward the end of Mary Jane's Mishap (1903), as seen in the still on the right. Both photos are Public Domain. Taken from Brighton & Hove, film and cinema.

In the article, Smith discussed his process and the technical details involved, explaining that, as good sunlight was paramount for proper lighting, he shot most of his films in the spring and summer (Middleton J. , 2015). According to Judy Middleton, a Sussex historian:

“Smith explained to the reporter that the easiest rate for taking photographs was 20 per second, which came to around 1,200 a minute, the standard rate at which they worked. … Every complete film was composed of around 25 yards of film with the photographs measuring about one inch across (the size of a postage stamp) with perforations on either side. It cost one sovereign every time a negative was taken and of course there were yards of wasted material. The images were thrown upon a sheet in the same way as a magic lantern operated” (Middleton J. , 2015).

In the promotional booklet Smith produced that year to promote his pleasure and amusement garden, he advertised: “High Class Lecture Entertainments with Magnificent Lime-Light Scenery and Beautiful Dioramic Effects". Additional attractions included: "Cinematographe. Displays of Animated Photography, Interesting and Sensational Moving Pictures (Gray, 2014). According to the British Film Institute, this illustrates that the relationship between film, lantern slides, and lantern projection, including the combining of still and moving images in a performance, held great interest for Smith. Like Méliès, Smith’s background in entertainment and his experience with magic lantern performances informed his filmmaking, providing a foundation on which to build and for which to explore this new medium. For example, Smith also converted into film the popular stories which he had already adapted into sets of lantern slides (Gray, 2014).

Smith would produce 31 short films that year, including the first football, also known as soccer, match ever exhibited, which he had complained was difficult to film, as the players soon ran beyond the range of the frame of the camera (Middleton J. , 2015). During this time, Smith explored and developed many film innovations. Indeed, according to film editor and professor, Don Fairservice: “on the evidence that exists, it seems that most of the pioneering development in the structure and editing of early films took place in Britain. … There was a conservatism that existed in the United States which seems to have been based on a principle that if a product was selling well and customers were satisfied, why alter it?” (Fairservice, 2001)

Among Smith’s early comedy shorts were a series of so-called “facials”, which are short films showing in medium closeup an individual’s facial expressions and reactions for the purpose of comedy and entertainment. Most are a simple one shot, medium closeup of a slightly evolving action; for example, a man drinking beer and gradually getting drunker, causing him to laugh and make rude gestures, as in 1897’s Old Man Drinking a Glass of Beer. According to film critic and historian, David Robinson, Smith’s records indicate that his wife, Laura Bayley, was involved directing some of the “facials” credited to her husband, including the Biokam “facial,” “Letty Limelight in Her Hair” (Robinson, 2002).

Old Man Drinking a Glass of Beer (1897) dir. George Albert Smith

Biokam, patented in 1898, was a complicated camera: part projector, printer, enlarger, reverser, snapshot camera, and cinematograph. The camera was made by the Brighton-based engineer, Alfred Darling, from whom Smith bought his first camera, (Christie's, 2022) possibly the Biokam used for this film. The Biokam was sold to the Warwick Trading Company, for whom G.A. Smith was processing commercial films (Science Museum Group, 2022).

But by 1900, Smith was progressing, including closeups, extreme closeups, inserted shots and point-of-view shots. An example of this can be seen in Smith’s three-shot comedy, As Seen Through a Telescope, where a man is shown looking through a telescope. The telescope is the means by which Smith shows the audience what the man with the telescope is viewing. This is an early example of a point-of-view shot, which is a shot that allows the audience to see what a specific character is looking at; therefore, the audience is seeing the shot from a specific character’s point of view.

As Seen Through the Telescope (1900) dir. George Albert Smith

The man with the telescope spies a gentleman walking his bike with a lady on the road. When the gentleman stops to fix the lady’s boot laces, the man uses his telescope to spy the maybe not-so-gentlemanly man taking advantage of the situation and using it as an opportunity to caress the lady’s ankle. This part of the scene allows for the insertion of a closeup point-of-view shot, where the audience views through the telescope the man on the road fondling the lady’s ankle, though this closeup isn’t technically a point-of-view shot. A point-of-view shot, or at least in modern terms, keeps its continuity by ensuring the illusion of a spatial area is intact, regardless of the angle and number of shots within that spatial area. Here, the closeup of the foot is shot against an unmatched interior background, thus destroying that continuity.

To give the audience the impression of looking through an object, a masked vignette was utilized to frame the shot, which is a shield placed in front of the camera to temporarily change the shape and/or dimensions of the screen (Librach, 2022). The telescope magnifying the event allows for Smith’s use of the closeup shot. When the lady’s laces are fixed, the man puts down his telescope so as not to be caught, and the couple passes by the man with the telescope, with the ungentlemanly man knocking the man who spied on them off his chair. This film was shot outside the Furze Hill entrance to St. Ann’s Well Gardens in Hove (Fisher, 2009).

Grandma's Reading Glass (1900) dir. George Albert Smith

Another of this type of film is 1900’s Grandma’s Reading Glass. This film is about a boy, probably played by Smith’s son, using his grandmother’s magnifying glass to magnify various objects, such as a bird in a cage, a cat, the gears of a pocket watch, and an extreme closeup of Grandma, showing her eye rolling and darting around in a silly fashion. Both films use a narrative device to justify the closeups, with Grandma’s Reading Glass utilizing the magnifying glass to magnify objects, and As Seen Through a Telescope using a telescope. But the closeups are lacking in portraying appropriate dimensions, as there is little attempt to keep any realistic relationship between the sizes of the objects the boy sees through the reading glass. The objects are simply sized to fit inside the circular mask. As in his film, As Seen Through a Telescope, Smith again uses a masked vignette to frame the shot and give the audience the impression of looking through an object—in this case, the magnifying glass (Librach, 2022).

In both films, Smith merely juxtaposes “regular” view with “close” view. And in both films, this juxtaposition is the whole point, used as an attraction instead of as a narrative tool. This practice no doubt borrows from the magic lantern shows of Smith’s past (Librach, 2022).

But by 1903, Smith stopped using masks to frame point-of-view shots, which then allowed such inserts to better add to the overall narrative structure of the film, rather than distract from it. As Ronald S. Librach states, “These masks [served to] announce … point-of-view shots …. When they’re “announced”—when our attention is drawn to them as examples of the filmmaker’s manipulation of his medium—they function primarily as “attractions,” not as clarifications of narrative situations” (Librach, 2022).

Narratively, Grandma’s Reading Glass is weaker than As Seen Through a Telescope, which uses the insertion of the POV-shot, not only within the context of, but to further the story—while Grandma’s Reading Glass seems to be more of a spectacle trick film. However, according to the British Film Institute:

“Grandma's Reading Glass was one of the first films to cut between medium shot and point-of-view close-up, though the editing is no more ambitious than this - in fact, there is very little narrative to speak of besides the boy looking around for further objects to examine. … The close-ups themselves were simulated by photographing the relevant objects inside a black circular mask fixed in front of the camera lens, which also had the effect of creating a circular image that helped them stand out from the rest of the film” (Brooke, 2014).

Another innovation was Smith’s early use of action continuity. Popular with audiences of the time were “phantom rides”, which were tracking shots produced by mounting a camera on the front of a moving locomotive, which functioned as an attraction to take audiences through beautiful, exotic locales—sort of like travelogues. According to editor Don Fairservice:

“Phantom rides provided spectators with a privileged view of, often, exotic landscapes as the train on which the camera was mounted made its way trough attractive foreign locations. Whenever the train passed into a tunnel the camera operator would stop turning or alternatively the showman would cut the unexposed tunnel section out. Smith’s plan was that the showman could introduce an entertaining diversion that would maintain the continuity of the journey, obviate the need for a jump cut, and thereby enhance the spectator’s pleasure” (Fairservice, 2001).

View from an Engine Front - Barnstaple (1898) dir. Unknown A good example of a typical 'phantom ride" film popular at the time.

The scene Smith filmed for insertion amid this phantom ride, entitled The Kiss in the Tunnel, was a voyeuristic shot of the train’s interior where a gentleman woos and then kisses a lady, who may or may not be his wife. The tension and possible discomfort of seeing this short scene might have been titillating and/or discomforting to its Victorian audience, but luckily, such tension was relieved by the gentleman realizing he had sat on his hat, deflating the hat, the man’s ego, and the brief moment of intimacy. The gentleman and lady are played by George Albert Smith and his wife, Laura Bayley. According to Don Fairservice: “being inserted into a tracking shot, Smith’s version of the Kiss in the Tunnel takes the spectator on the journey with the couple …” (Fairservice, 2001).

A Kiss in the Tunnel (1899) dir. George Albert Smith

Smith probably had an idea of how to create action while maintaining continuity from one shot to the next because he explicitly referred to the cut from the kiss back to the phantom ride in his sales catalogue. But even with this alleged knowledge, the shot of the kiss was destined to function as an attraction unto itself rather than maintaining the illusion of spatial continuity (Librach, 2022).

Another example of Smith’s contributions to filmmaking is his film Santa Claus, from 1898, which is probably the oldest extant Christmas film. According to the British Film Institute, this film contains the earliest known example of parallel action. Parallel action is when two or more separate actions, often taking place in separate locations, are intercut to give the impression that they are taking place at the same time. They can also be used to illustrate a connection or contrast between said scenes, to create one total narrative.

Santa Claus (1898) dir. George Albert Smith

In Smith’s film, Santa Claus, two sleepy children on Christmas Eve are going to sleep. Dr. Frank Gray believes the children to be played by Smith and Bailey’s son and daughter (Gray, Smith the Showman: The Early Years of George Albert Smith, 1998). When the nanny turns off the lights, the background goes black, courtesy of a jump cut, to indicate the lack of light, while the children and the floor remain illuminated. When the lights go out, a superimposed image, shot inside of a circular mask, appears in the upper right of the frame, showing Santa Claus appearing on the rooftop and sliding down the chimney—this was created using double exposure. The parallel action occurs when we, the audience, see both the children sleeping inside the house, and Santa’s actions on the roof at the same time, as though these scenes are happening simultaneously—even though they are occurring in separate locations.

When he slides down the chimney, the scene in the circular mask disappears and Santa is seen arriving in the home to deliver presents. Before the children can awaken, Santa Claus then disappears via another jump cut (Brooke, Santa Claus (1898), 2014). Furthermore, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, the use of superimposition in this film marks Smith’s Santa Claus as the earliest surviving example of double exposure in a film (Guiness Book of World Records, 2022).

Indeed, according to ACMI, Australia’s national museum for the moving image, in 1897, Smith patented his own double-exposure system (ACMI, 2022). Smith may have utilized his own patented double exposure system in 1898, when producing The Mesmerist and Photographing a Ghost.

Both The Mesmerist and Photographing a Ghost see Smith creating films from a world with which he’d been intimately involved. After all, he had been a mesmerist, understood the public’s fascination with spiritualism, and was involved in the Society for Psychical Research’s attempts to prove that ghosts were telepathic hallucinations. Having been involved in these fields, he probably had a good understanding of the trickery that was involved in ghost photography. Photographing a Ghost is now lost, but the description in the Edison catalogue for the film’s distribution states:

“Shows what can be done by an enthusiastic amateur with a 4x5 Kodak. The picture reveals the artist with his camera in position. Two men come in with a trunk, labelled GHOST. The photographer carefully opens the trunk, and up rises a tall, white Thing. It glides around, and just as the artist is ready, it disappears. He is greatly mystified; and more so than ever, when the ghost reappears, apparently from nowhere, and after floating around, steps back into the trunk. The photographer promptly sits on the lid and locks it with an air of relief. He gets up, turns around, and there stands Mr. Ghost, behind him. The ghost becomes active, and chairs are thrown around in a very lively fashion. The photographer finally sinks down in despair and gives up the job” (Fisher, Films made in the Brighton & Hove area: The silent era, 2015).

As another contemporary description of the film uses a form of the word “amusingly” twice when describing the actions of the ghost, who the writer of this description describes as a “ghost of a swell” (Leeder, 2017). Smith is probably playfully mocking spirit photography in this film, which similarly showed ghosts in a semitransparent manner. According to David Fisher, former editor of Screen Digest and curator of the website, brightonhistory.org.uk, Smith may also have been influenced by the illusion, “Pepper’s Ghost”, which we discussed in the previous episode. Smith reused this special effect when portraying the ghost in Mary Jane’s Mishap, which we briefly discussed at the end of Episode 2. While not necessarily a horror film, Photographing a Ghost is one of the earliest-known examples of ghosts on film, and, influenced by their appearance in spirit photography, brought this visual of ghosts and the paranormal to a larger audience and influenced future film portrayals of them, including in the 1937 film, Topper, starring Cary Grant and Constance Bennet—which is one of my favorite films.

The scene where the main character George and Marion first become ghosts in Topper (1937), as seen in flashback in the sequel, Topper Takes a Trip (1938).

Another film by G.A. Smith that is sometimes considered a horror film, but usually considered to be a comedy, is “The X-Rays”, from 1897. Starring Smith’s wife, Laura Bayley, and Tom Green, the star of the previously-mentioned “facial”, “Old Man Drinking a Beer”, “The X-Rays” is a cute 45-second film about a pair of lovers who are briefly shown as they look when photographed by an x-ray machine. Flirting while sitting on a bench, the gentleman kisses the bashful lady’s hand, with the pair looking as though they might be preparing to pose for a photograph; however, the couple is being photographed by an x-ray machine—for reasons that are never explained. The machine is turned on and, using a jump cut, the flirting couple are now shown in their skeletal form, including the only part of the lady’s parasol now visible being the boning. The lady still has the faint outline of her transparent dress visible, while no outline of clothes is visible on the gentleman—I have seen it suggested that this may be because of the modesty of Victorian times, but it also creates a more interesting and charming visual. The x-ray camera turns off and, through another jump cut, we see the couple return to their normal state. Finally, the gentleman’s romantic advances become a little too amorous, so the lady swats at him and leaves, leaving the gentleman unhappily pouting. While not a horror film, the film does provide an early visual for skeletons coming to life and interacting with one another.

The X-Rays (1897) dir. George Albert Smith

This was a very topical comedy for Smith. Smith’s company accounts record that this film was made in October of 1897, which was less than two years after the discovery of x-rays in November of 1895 by physicist Wilhelm Röntgen, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901 for the discovery. As a side note, upon first discovering the rays, Röntgen was unsure of their nature, and so, to represent the unknown elements of the rays, called them “X” (Nobel Prize Outreach, 2022). A true humanitarian, Röntgen refused to patent his discovery, as he wanted it to be accessible for all (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022).

However, as early as only a few months after Röntgen’s discovery, electromagnetic waves became the latest craze. Yes--“x-ray-mania” had arrived!

The interest in and popularity of x-rays meant that references to them were appearing throughout various forms of media, infecting the pop culture of the time. According to Dr. Chris Impey and Professor Holly Henry: “… some speculated at the time that the new technology might afford a kind of X-ray vision that might make it possible to capture on film the images of ghosts, apparently a popular notion in Engand” (Impey & Henry, 2013).

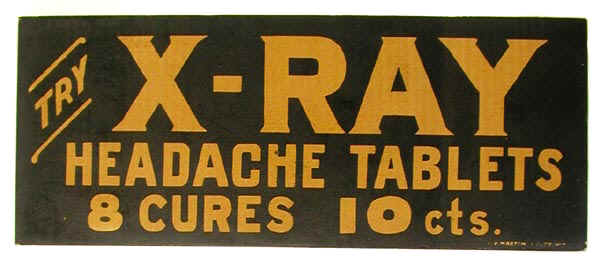

Dr. Edwin Gerson further elaborates: “This amazing ‘new light’ caught the public's imagination. . . [I]ts name quickly became synonymous with cutting-edge technology and also functioned as a metaphor for ‘powerful unseen truth and strength.’ X-rays, many believed, would become a part of everyday culture, from henhouses to the temperance movement, from the detection of flaws in metal to the analysis of broken hearts. There was an immediate popular response that spawned the sort of cultural manifestation common to fads. The public was simply astonished with x-rays, and advertisers played off this spellbound attention by adding the name to almost any type of product. X-rays appeared in advertising, songs, and cartoons” (Gerson, 2003).

Products that capitalized on the sudden market created by the popularity of x-rays included headache tablets; disease-preventative prophylactics; golf balls; and stove polish (Gerson E. S., 2004).

Like many fads and other aspects of pop culture, the intense popularity of x-rays meant that they were ripe for use in comedy and other forms of entertainment. With the film, “The X-rays”, G.A. Smith was able to find an inventive way to utilize the subject of x-rays within the narrative of his trick film. David Fisher suggests that Smith may have been influenced in the subject matter of his film by James Williamson’s purchase of an x-ray machine (Fisher, Films made in the Brighton & Hove area: The silent era, 2015).

James Williamson was another early filmmaker who was a chemist by trade and owned his own pharmacy. He then used this education to pursue his interest in film, firstly, by processing photographs and performing magic lantern shows, before finally creating moving pictures. In 1886, Scottish-born Williamson, who moved to England as an adolescent, moved his pharmaceutical and photographic businesses to Hove, first living above his shop at 144 Church Road (Fisher, Brighton & Hove from the dawn of the cinema, 2012) before settling at 55 Western Rd. (The Regency Society, 2022).

Attack on a China Mission (1900) dir. James Williamson

Like Smith, Williamson proved Brighton and Hove to be an important place in early film history. For example, Williamson’s Attack on a China Mission, from the year 1900, is described by the late British film historian, John Barnes, as “the most fully developed narrative of any film made in England up to that time” (Brooke, Attack On a China Mission (1900), 2014). Based on the then-contemporary Boxer Rebellion and filmed in Hove at a house known as Ivy Lodge, where the current area of Vallance Gardens is now located, Williamson’s film had a cast of at least 24 actors and included four shots, one of which was a reverse-angle cut, which is a cut to a shot of the action shown from the opposite direction from the previous shot, normally utilized to show the opposite point of view. This type of shot did not start to become regularly used until about a decade later. While a cast of 24 and four shots may not sound impressive, consider that Williamson accomplished this feat when most films of this era were only composed of one or two shots and only consisted of a small number of performers.

L'Affaire Dreyfus (1899) dir. Georges Méliès

As film historian and writer Michael Brooke states: “Williamson was following in the footsteps of Georges Méliès, whose eleven-scene dramatised documentary L'Affaire Dreyfus (1899) was very influential on British film-makers, many of whom made similar dramatisations of the events of the ongoing Boer War. But Williamson's film comfortably outstripped them in scale and ambition” (Brooke, Attack On a China Mission (1900), 2014). Unfortunately, less than half of the film currently survives.

James Williamson and George Albert Smith are two of the most influential members of the film pioneers associated with what French film historian Georges Sadoul would later call “The Brighton School”; though the Cinematheque Francaise would later dismiss the term as “a convenience for later commentators”. The other two filmmakers normally associated with “The Brighton School” are Esme Collings and Alfred Darling. Alfred Darling, as we have already mentioned in this episode, was the Brighton-based engineer who invented the Biokam and sold G.A. Smith his first camera.

“The Brighton School” of filmmakers seems to mostly be defined by the fact that all the members were active around the same time and in the same area, though David Fisher points out that most of this work was filmed in Hove, rather than Brighton (Fisher, The history, 2022). Indeed, groups of independent film producers were active in many parts of England, as London was not the centralized seat of British film production until around 1915 (Librach, 2022).

James Williamson himself stated that he believed it was a coincidence that they all were active in Brighton at the same time. While Brighton owed much of its use as a filming location to its natural beauty, Williamson stated that the key ingredient in allowing the Brighton-based filmmakers to progress in the medium was the assistance of Alfred Darling, whom Williamson calls “a clever engineer who made a study of the requirements of film producers.” Williamson claims that it was only after meeting Darling that his filmmaking began in earnest (Fisher, The history, 2022).

Instead, the fundamental connection between many of the English filmmakers of the early years of cinema seems to be American-born film producer and distributor, Charles Urban. In fact, Urban was also associated with Georges Méliès, being the English distributor of Méliès’ films and collaborating with him on a film production. And it was through that film production that George Albert Smith was able to work with Méliès.

Charles Urban was a Cincinnati-born entrepreneur who, in 1895, came to manage a kinetoscope-photograph parlor in Detroit, before acquiring the Michigan rights to the Edison vitascope the following year. While touring Michigan and staging exhibitions of Edison vitascope films, he modified a vitascope to increase the capacity of the take-up reel, or the reel that gathers up the film that has already been projected. Urban then commissioned New York phonograph engineer Walter Isaacs to create a hand-crank projector that integrated the Urban-designed higher capacity take-up reel, with the use of the hand crank allowing the projector to be operated without the use of electricity. This projector became known as the Bioscope and was completed in 1897, the same year as Urban left the U.S. In August of that year, Urban became the manager of the London office of the New York-based firm, Maguire and Baucus, (Librach, 2022) which had gained the exclusive rights to sell and exhibit Edison’s kinetoscopes and kinetoscope films in Mexico, the West Indies, Australia, South America, Europe and Asia (Rutgers, 2022).

In late 1894, Maguire and Baucus also established the Continental Commerce Company, which handled their business in Africa, Europe, and this was the name under which Maguire and Baucus did business in England. Only a month after taking over the London office, Urban moved the Continental Commerce Company to Warwick Court in London. In December of that year, Maguire and Baucus found itself at the center of a lawsuit brought by Edison for infringement of his motion picture patents (Rutgers, 2022). The following May, Urban reincorporated the Continental Commerce Company as the Warwick Trading Company, naming it after its location of Warwick Court, as he believed it to be “a good, solid British name” (Librach, 2022).

During this same period, Urban began making important business connections, one of whom was Cecil Hepworth. Urban commissioned Hepworth, at that time an inventor of photographic equipment, to fix some remaining issues with his projector, the Bioscope (Librach, 2022). Hepworth would later become an influential filmmaker. According to Dr. Simon Brown, associate Professor of Film and Television at Kingston University London, “A producer, director, writer and scenic photographer, Cecil Hepworth survived in the film business longer than any other British pioneer film-maker. … In the course of his career, Hepworth became one of the most respected, if not the most dynamic, figures in British cinema” (Brown, 2014).

The London-born Cecil Hepworth was the son of noted magic lantern showman, Thomas Cradock Hepworth, often credited as T.C. Hepworth. T.C. Hepworth, is also who, incidentally, succeeded John Henry Pepper, the showman who popularized Pepper’s Ghost, when Pepper fell out with the governing board at the Royal Polytechnic on Regent Street in London (Secord, Quick and Magical Shaper of Science, 2002).

1898 proved to be an important year for Charles Urban, for not only was he manufacturing his Hepworth-modified Bioscope, but he also acquired Alfred Darling’s Biokam. But more importantly, this is when he secured the distribution rights to important filmmakers, such as George Albert Smith, James Williamson, and Georges Méliès. As the turn of the century was approaching, filmmaking was changing in fundamental ways. By 1905, the age of the nickelodeon was dawning, and as the late film historian and writer, Carlos Clarens stated: “Trickery for the sake of trickery lost much of its allure during the nickelodeon era (Clarens, 1997).

The spectacles that were the basis for trick films had grown out of the magic lantern tradition. During the first few years of moving pictures’ existence, no subject was necessary—just the wonder of seeing images move was enough for the audience, as the filmmaker James Williamson later stated: “The subject did not matter. To see waves dashing over rocks in a most natural way, to see a train arriving and people walking about as if alive was admitted to be very wonderful” (Librach, 2022). According to Tim Gunning, Professor Emeritus of Art History, Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Chicago, trick films are “a series of displays, of magical attractions, rather than a primitive sketch of narrative continuity. … Such viewing experiences related more to the attractions of the fairground than to the traditions of the legitimate theater [and reveal a] fascination with the thrill of display rather than the construction of a story” (Librach, 2022).

During this period, moving pictures competed with music-hall and fairground attractions, as well as various photographic attractions, such as the magic lantern show. Cecil Hepworth, who had grown up with his father presenting magic lantern shows at the Royal Polytechnic on Regent Street in London, remembered the thrill of viewing the attractions at Marlborough Hall and the theatre alongside it. Dr. Helen Groth of the University of New South Wales notes when discussing Cecil Hepworth’s autobiography, Came the Dawn, that the theatre:

“included a projection room that spanned the whole width of the theatre at dress circle level and contained upwards of fifteen limelight magic lanterns of various sizes set up to project a mixture of large painted and photographic slides, as well as trick slides of revolving geometrical patterns that created the illusion of movement on the screen. There was also a curious device known as a ‘Choreutoscope’ that Hepworth notes anticipated the modern cinematograph” (Groth, 2013).

As a side note, the Choreutoscope was a magic lantern type of mechanism, popular from about 1866-1880, that contained six glass plate slides. These slides, which contained drawings, often skeletons, on a black background, were then mounted on a projector with a Maltese cross intermittent movement mechanism, which allowed the slides to change in quick succession. This projector was the first to use an intermittent movement, and this system would become the basis for cinema-based cameras and projectors (National Media Museum, 2022).

Moving pictures had to compete with these types of well-known and loved theatrical spectacles. As the filmmaker James Williamson later commented, “It has to be remembered that the public up to this date had been accustomed to looking at lantern slides of exquisite photographic quality—single pictures upon which much time and skill had been spent. It was not easy to persuade people that photographs fit to look at could be produced by the yard by simply turning a handle” (Librach, 2022).

When showing films during his early traveling showman days, Cecil Hepworth almost seemed to act as a modern DJ in terms of interpreting and mixing the demonstration of the films as DJs do with records:

“[T]hough my first attempts at the traveling show business consisted of a half a dozen forty-foot films from [R.W.] Paul’s junk basket, plus a little music and a hundred or so lantern slides, it required considerable ingenuity to spin that material out to an evening’s entertainment. I showed the films forwards in the ordinary way and then showed some of them backwards. I stopped them in the middle and argued with them; [I] called out to the little girl who was standing in the forefront of the picture to stand aside, which she immediately did. That required careful timing but was very effective. … but with it all, I very soon found I must have more films and better ones” (Librach, 2022).

Because of this, many of those who produced trick films and were active at the beginnings of film had backgrounds as magicians, theatrical showmen, and magic lantern lecturers. Indeed, this was not simply a background of filmmakers in the west. D.G. Phalke, popularly referred to Dadasaheb Phalke, is often considered the Father of Indian cinema (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2022). Phalke was responsible for the first Indian feature film and claimed credit for the birth of the Indian film industry, a claim which film scholar Ashish Rajadhyaksha states “is hardly an exaggeration …” (Rajadhyaksha, 1986).

Like Méliès and Smith, Phalke had a background in magic and theatrics, among other pursuits (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2022). Then, at the age of 40, as Méliès and Smith had experienced at an exhibition of the Lumiere Brothers’ cinematographe 14 years prior, Phalke had an experience that changed his life. Of his viewing of The Life of Christ, by French female pioneering director Alice Guy-Blache, Phalke later stated:

“That day … marked the beginning of a revolutionary change in my life. That day also marked the foundation in India of an industry which occupies the fifth place in the myriad of big and small professions that exist … while [The Life of Christ] was rolling before my eyes I was mentally visualizing the gods Shri Krishna, Shri Ramachandra, their Gokul and Ayodhya … Could we, the sons of India, ever be able to see Indian images on the screen […] (Rajadhyaksha, 1986).

The Birth, the Life, and the Death of Christ (1906) dir. Alice Guy-Blanche and Victorin Jasset

While initially filming trick films, like Growth of a Pea Plant, Phalke traveled to London in 1912, where he met Cecil Hepworth, who had established his own film studios in 1899. Hepworth showed Phalke his studio and illustrated the film equipment, recommending to Phalke that he purchase such equipment if he wanted to begin making films. While in England, Phalke purchased a perforator, Kodak stock, and a Williamson camera (Dissanayake & Gokulsing, eds., 2013) manufactured by the filmmaker James Williamson, who in 1910 had begun to focus on manufacturing film equipment (The Kodak Collection at the National Media Museum, Bradford, 2022).

And like many of his western counterparts, Phalke found himself neglected by the very industry which he nurtured and helped to establish. Forgotten, penniless, and bitter at the time of his death, Phalke stated, “I am very much disappointed about the creations of Indian Film Industry. With what ideals and with what long-drawn-out suffering I built up this indigenous industry and what it is my misfortune to see today!” (Dissanayake & Gokulsing, eds., 2013). However, more than 25 years after Dadasaheb Phalke’s death, the National Film Awards, India’s most prestigious cinema-related award ceremony, named their lifetime achievement award in his honor.

By the turn of the century, a focus on the narrative, instead of the pure spectacle of trick films, was quickly becoming the standard, as evidenced by the increasing commonality of the multishot film (Librach, 2022). These shots existed to mediate and enhance the telling of the story, rather than to impress its audience as another visual “trick”. This era of transition between the age of trick films and the nickelodeon era found that while films were advancing in many ways, especially technically, narratively, many were still stuck in the past of the magic lantern shows.

The Big Swallow (1901) dir. James Williamson

For example, James Williamson’s 1901, three-shot trick film, The Big Swallow—while hailed by film historian and writer Michael Brooke as “one of the most important early British films in that it was one of the first to deliberately exploit the contrast between the eye of the camera and of the audience watching the final film” (Brooke, Big Swallow, The (1901), 2014)--as it is described in Williamson’s sales catalogue, shows the film’s reliance on and the necessity of exhibitors narrating and explaining the actions in the film, as would have been done in a magic lantern lecture. For film to progress, the narrative would instead need to be communicated to the audience via cinematic devices, such as shots, editing, and angles, that control and manipulate the audience’s attention, which Tim Gunning notes are techniques of the “classical system of continuity”. As stated by Tim Gunning, “The classical film can absorb sudden ubiquitous switches in viewpoint into an act of storytelling, creating a cinema whose role is less to display than articulate a story. The continuity of classical cinema is based on the coherence of the story, and the spectator’s identification with the camera is mediated through an engagement with the unfolding of the story” (Librach, 2022).

However, some filmmakers, like George Albert Smith and James Williamson, began to transition into other parts of the film business which eventually overtook their directing efforts. Already in 1898, the same year that he made Santa Claus and Photographing a Ghost, Smith was also processing and printing film for fellow filmmakers, like James Williamson, and for Charles Urban’s Warwick Trading Company, among numerous others. While Smith’s success in film during this period meant that in late 1898 and early 1889, his films were presented alongside Georges Méliès’ at the Alhambra Theatre in Brighton; Smith’s simultaneous success with the Warwick Trading Company meant that by 1900 the company helped to finance the construction of a film studio at St. Ann’s Well Gardens (Fisher, Brighton & Hove from the dawn of the cinema, 2012).

Offered a two-year contract by the Warwick Trading Company, Smith was described that year in the Warwick Trading Company’s catalogue as “Manager of the Brighton Film Works of the Warwick Trading Company”. This is also the year that Smith produced, among other films, As Seen Through a Telescope and Grandma’s Reading Glass.

In January of 1901, Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom died, and Britain entered the Edwardian era. The coronation of Edward VII and his Queen Consort, Alexandra, took place over a year and a half after Queen Victoria’s death, on August 9, 1902, at Westminster Abbey. This would be the first coronation in over 60 years. For royal context, the new king, Edward VII, the son of Queen Victoria, was the grandfather of George VI, who was portrayed onscreen by Colin Firth in The King’s Speech, and of the scandalous Edward VIII, known after his abdication as the Duke of Windsor. And for those not up on their modern British royal family history, that means Edward VII was the late Queen Elizabeth II’s great-grandfather.

Though the official website of the British royal family claims that “The coronation of the new Sovereign follows some months after his or her accession, following a period of mourning and as a result of the enormous amount of preparation required to organise the ceremony,” (The Royal Household, 2022) I see no instance of a coronation taking place less than a year after the previous monarch’s death since the coronation of George IV in 1821, which took place a year and a half after he acceded to the throne—though George VI did hold his coronation within a year of his brother’s abdication.

As in modern times, the British Royal family of the Victorian and Edwardian eras seem to have had innate understanding of the power of the media and, as her Diamond Jubilee approached in 1897, Queen Victoria showed an astute understanding of public image and the power of photography and film. For example, for her “official portrait”, she chose a photograph taken four years earlier. While Queen Victoria required the name of the photographer be cited whenever the photograph was used, she also had the copyright removed—allowing her image to be put on an infinite variety of products and items for mass consumption, “from biscuit tins to tea towels”, and ensuring her image was ubiquitous (Merck, ed., 2016).

On June 22, 1897, three million people gathered to watch the Queen’s procession, with cameramen placed at various points on the six-mile route to fully capture the event. Robert W. Paul, the inventor of the theatrograph, which we briefly discussed in episode 1 as being the first motion picture camera bought by Méliès, was one of the many filmmakers present at the Jubilee: “Large sums were paid for suitable camera positions, several of which were secured for my operators. I myself operated a camera perched on a narrow ledge in the Church yard” (Merck, ed., 2016).

Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee (1897) dir. Unknown

Such films are known as actualities and, according to the late film historian, John Barnes: “These films complimented news coverage of the events represented, and provided a visual corollary to the descriptions in the popular press. Like the panoramas, dioramas, and wax museums of the late nineteenth century, they were not so much sources of news in themselves as representations of current events already familiar from other sources” (Barnes, The Beginnings of the Cinema in England, 1894-1901: Volume 5. , 1996).

The response from the crowd upon seeing the Queen during her procession was surprising to and overwhelming for her, as she wrote in her diary: “No-one ever I believe, has met with such an ovation as was given to me, passing through those 6 miles of streets, including Constitution Hill. The crowds were quite indescribable, & their enthusiasm truly marvelous & deeply touching. The cheering was quite deafening, & every face seemed to be filled with real joy. I was much moved & gratified” (Merck, ed., 2016). Films of the Queen’s Jubilee proved to be very popular and profitable for film producers and distributors and became a focal point of many film exhibitions.

The effect of the Jubilee being filmed and exhibited was to allow those who were normally unable to witness such an event, such as the disabled and/or the poor, and particularly those living in remote locations, to experience an occasion of national importance and afford them a sense of participation and national identity. Fairground exhibitors, which catered to the poor in rural and/or industrial areas, found film of the Jubilee to be so popular that they were forced to increase the number of showings. The late film historian, John Barnes, states “[Exhibition sites] varied in scale from grand Bioscope Shows in tents capable of holding as many as 500 spectators, to peep-show street cinematographes with eyepieces for twenty people” (Barnes, The Beginnings of the Cinema in England, 1894-1901: Volume 5. , 1996).

Even this early in film’s history, royal patronages were being sought by film producers and partnerships for exclusive access and rights were already being formed. British inventor, William Dickson, who had invented the kinetoscope for Edison, had helped to form the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company in 1895, before returning to Britain two years later to work for its British branch. Approximately a decade later, the company would be known as the simpler Biograph Company, and is remembered as the studio for whom D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, and Lillian Gish, among others, worked. On the Prince of Wales receiving the honor of the Order of Bath, a banquet was held, after which the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company was invited to St. James Palace to present an exhibition of films, including parts of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee procession.

According to film scholar, Ian Christie:

“The British Mutoscope and Biograph … appears to have adopted a deliberate policy of courting royal relationships, possibly in order to counteract the dubious reputation of its Mutoscope subjects, which often featured titillating images of glamorous women. In the summer of 1897, their record of Afternoon Tea in the Gardens of Clarence House showed three generations of the royal family at a garden party with what Richard Brown and Barry Anthony term ‘startling informality’. British Bioscope’s relationship with the royal family continued to bear fruit after the St James’s Palace showing. They filmed the Queen laying the foundation stone of the Victoria and Albert Museum on 17 May 1899, while a Biograph show was given at Sandringham on 29 June. And in the summer of 1900, Biograph filmed what is probably the most important of the early ‘intimate’ royal films, [Children of the Royal Family of England], which showed ‘our future king at play’ – namely Prince Edward of York, later Edward VIII. This two-part film, made over two mornings, was a major success for the company, becoming an extremely popular item in Biograph programmes at the Palace Theatre, and later on their home-viewing system, the Kinora. And Biograph’s relationship with the future king, Prince Albert, soon to be Edward VII, would continue, as they filmed many events throughout his reign” (Merck, ed., 2016).

This presented film producers from competing companies with a problem, as the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company had exclusive rights to film the coronation inside Westminster Abbey.

The answer as to how to compete with British Mutoscope and Biograph: a reconstructed actuality, also known as a reconstructed newsreel; like what we know today as a docudrama.

In 1902, Urban’s success with the Warwick Trading Company led him to open a Paris branch. Again, Urban was already associated with the Montreuil-based George Méliès, as the English distributor of his films. George Méliès had been creating reconstructed actualities since 1897, with a series based on the Dreyfus Affair, which were sympathetic in its presentation of Dreyfus, being among Méliès’ best known.

Méliès’ sympathetic portrayal served as powerful propaganda, as many actualities and reconstructed actualities did, and as many films, such as Casablanca, still do—though it wasn’t the content of the images as much the context of the exhibition that were propagandistic. Nonetheless, so divisive was public opinion regarding Dreyfus that fights broke out in the audience during exhibitions of Méliès’ films. The French Government ended up banning Méliès’ film series, as well as one produced by Pathé, and hindered its distribution internationally—though probably more to protect its own reputation amid national and international outcry and charges of antisemitism (Barnes, The Beginnings of the Cinema in England, 1894-1901: Volume 5., 1996).

Urban tackled the challenge of competing with the British Mutoscope and Biograph by commissioning the great Méliès to create a reconstructed actuality of Edward VII’s upcoming coronation. According to Dr. Richard Abel, Professor Emeritus of International Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Michigan, The Coronation of Edward VII “was quite different from L’Affaire Dreyfus and much closer to the tableau vivant style that would soon characterize the historical film” (Abel, 1998).

The Coronation of Edward VII (1902) dir. Georges Méliès

While Méliès is famous today for his fanciful sets and creative details, historical accuracy was of the utmost importance to compete with the Mutoscope and Biograph’s footage of the actual coronation. Indeed, Méliès and his co-producer were so determined to create an authentic representation of the event that they even visited Westminster Abbey, which Méliès then attempted to faithfully recreate at his own greenhouse-like studio in Montreuil. After all, if Méliès could create military reenactments of the Greco-Turkish war in a Parisian garden (Barnes, The Beginnings of the Cinema in England, 1894-1901: Volume 5.,1996), he could certainly recreate Westminster Abbey within the confines of his studio.

Additionally, Urban insisted on the use of his own camera, the Bioscope, during the production of this film. As this was a pre-enactment, having been filmed prior to the actual coronation, to be printed and shipped to exhibitors in time for its premiere on the date of the coronation on the 26th of June, Méliès had to depend on the ritual of the ceremony to anticipate the actions of the British royals. Ever the world of make-believe that filmmaking is, the actor playing the new king was a washroom attendant, cast for his supposed likeliness to Edward VII (Abel, 1998). According to multiple sources, including former editor of Screen Digest, David Fisher and film critic and author David Robinson, George Albert Smith worked with Méliès on this film. Indeed, Dr. Frank Gray states that Méliès and Smith were acquaintances who corresponded with one another during this period (Gray, George Albert Smith, 2022).

According to multiple sources, including former editor of Screen Digest, David Fisher and film critic and author David Robinson, George Albert Smith worked with Méliès on this film. Indeed, Dr. Frank Gray states that Méliès and Smith were acquaintances who corresponded with one another during this period. (Gray, George Albert Smith, 2022)

But I am unable to clarify exactly what function Smith served in the making this film, especially considering that, at this point in his life, Smith was a successful businessman, showman, and filmmaker with his own studio and lab. However, as this film was an international coproduction commissioned by Urban on behalf of the Warwick Trading Company, I’m guessing that Smith was involved in relation to his role as the manager of the Brighton Film Works of the Warwick Trading Company, which is how Smith was listed in the Warwick Trading Company’s catalogue. I speculate that, perhaps, Smith acted as a representative of Urban and the company in this international coproduction and functioned in an intermediary role—a role that would have benefitted from Smith and Méliès’ acquaintanceship. As Urban even wanted his own camera used in the filming, perhaps Smith monitored the production and assisted with the use of Urban’s film equipment. This would also allow an Englishman to monitor for cultural considerations.

Whatever the case may be, the film was ready for exhibition by the coronation’s date on the 26th of June, when, three days before the coronation was to occur and, therefore, the film’s premiere, an announcement was made by the Palace that the coronation was being delayed—the 60-year-old Edward VII had been stricken with appendicitis. The coronation finally occurred a month and a half later, on the 9th of August, with Méliès’ film premiering that same day, headlining at the Alhambra Music Hall in Leicester Square in London. (Christie, 2016) Urban bookended the film with actual footage of the royal coach’s arrival and departure, to complete the pseudo-newsreel quality. (Librach, 2022)

Unused footage of the Coronation of Edward VII procession (1902)

An immediate hit, Méliès and Urban’s The Coronation of Edward VII made the rounds on the Empire Palace music hall circuit in England, before embarking on a world tour as ostensibly the first royal documentary. (Abel, 1998) According to Ian Christie: “Urban’s investment in this coverage, and that of the other companies, confirm that the advent of the photographic image, both still and moving, had made the British monarchy a highly marketable spectacle. (Christie, 2016)

Beyond making The Coronation of Edward VII, 1902 was a peak year for Méliès and Smith, with Smith also producing Mary Jane’s Mishap, while Méliès produced his well-remembered and beloved A Trip to the Moon. But by the following year, events were beginning to transpire that would affect the future of not only Méliès, Smith, and Urban, but of filmmaking itself.

Please subscribe to Rhapsody in 35MM wherever you listen to your podcasts. Also, subscribe to this website so you will be alerted to new postings such as this. Please make sure to follow us on the social media platform of your choice -- the links can be found on this website. Please make sure to rate us and comment on Apple podcasts, or wherever you listen to podcasts. Until next time!

Sources

Abel, R. (1998). The Cine Goes to Town: French Cinema, 1896-1914, Updated and Expanded Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press.

ACMI. (2022). George Albert Smith. Retrieved from ACMI: https://www.acmi.net.au/creators/45307--george-albert-smith/

Amberley Publishing. (2020). Judy Middleton. Retrieved from Amberley Publishing: https://www.amberley-books.com/author-community-main-page/m/community-judy-middleton.html

Barnes, J. (1996). The Beginnings of the Cinema in England, 1894-1901: Volume 5. . Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1996.

Barnes, J. (2022). Alfred Darling. Retrieved from Who's Who of Victorian Cinema: https://www.victorian-cinema.net/darling.php

British Pathe. (2022). 1890s Traffic Scenes. Retrieved from British Pathe: https://www.britishpathe.com/gallery/1890s-traffic/5

Brooke, M. (2014). Attack On a China Mission (1900). Retrieved from BFI Screen Online: http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/520615/index.html

Brooke, M. (2014). Big Swallow, The (1901). Retrieved from BFI Screen Online: http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/444628/index.html

Brooke, M. (2014). Grandma's Reading Glass (1900). Retrieved from BFI Screen Online: http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/443114/index.html

Brooke, M. (2014). Santa Claus (1898). Retrieved from BFI Screen Online: http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/725468/

Brown, S. (2014). Hepworth, Cecil (1874-1953). Retrieved from BFI Screen Online: http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/450004/

Christie, I. (2016). The British Monarchy On Screen. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Christie's. (2022). Biokam camera no. 234. Retrieved from Christie's: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4320152

Clarens, C. (1997). An Illustrated History Of Horror And Science-fiction Films: The Classic Era, 1895-1967. Cambridge: Da Capo Press.

Dissanayake, W., & K. Gokulsing, e. (2013). The Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas. London: Routledge.

Fairservice, D. (2001). Film Editing - History, Theory and Practice: Looking at the Invisible. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Fisher, D. (2009, July 13). Films made in Brighton & Hove: As Seen Through a Telescope. Retrieved from Brighton On Film: https://web.archive.org/web/20120322002732/http://www.terramedia.co.uk/brighton/brighton_films_telescope.htm

Fisher, D. (2012). Brighton & Hove from the dawn of the cinema. Retrieved from Brighton & Hove, film and cinema: https://web.archive.org/web/20150811070923/http://brightonfilm.com/brighton_chronology.htm

Fisher, D. (2012). Cinema-by-Sea: Film and Cinema in Brighton & Hove Since 1896. Brighton: Terra Media Ltd.

Fisher, D. (2015). Films made in the Brighton & Hove area: The silent era. Retrieved from Brighton History: https://www.brightonhistory.org.uk/film/films/films_made_in_brighton_silent.htm

Fisher, D. (2022, June 28). The history. Retrieved from Brighton & Hove, film and cinema: https://www.brightonhistory.org.uk/film/film_history1.html

Gerson, E. (2003). X-ray Mania: The "X-Ray" in Advertising, Circa 1895. Retrieved from Abstract Archives of the RSNA, 2003: http://archive.rsna.org/2003/3300013.html

Gerson, E. S. (2004). Scenes from the Past: X-ray Mania: The X Ray in Advertising, Circa 1895. Retrieved from RadioGraphics: https://pubs.rsna.org/doi/full/10.1148/rg.242035157

Gray, F. (1998). Smith the Showman: The Early Years of George Albert Smith. Film History, 8-20.

Gray, F. (2014). Smith, G.A. (1864-1959). Retrieved from BFI Screen Online: http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/449633/index.html

Gray, F. (2022). George Albert Smith. Retrieved from Who's Who of Victorian Cinema: https://www.victorian-cinema.net/gasmith

Groth, H. (2013). Moving Images: Nineteenth-Century Reading and Screen Practices. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Guiness Book of World Records. (2022). Earliest surviving use of double exposure in a movie. Retrieved from Guiness Book of World Records: https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/107460-earliest-surviving-use-of-double-exposure-in-a-movie

Henry, H., & Impey, C. (2013). Dreams of Other Worlds: The Amazing Story of Unmanned Space Exploration. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Leeder, M. (2017). The Modern Supernatural and the Beginnings of Cinema. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Librach, R. S. (2022). The Illustrated Guide to Early Cinema. Retrieved from Cinematheque Froncaise: http://cinemathequefroncaise.com

Mandy Merck, e. (2016). The British Monarchy On Screen. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Middleton, J. (2015). Hove in the Past. Retrieved from St. Ann's Well Garden, Hove: Judy Middleton, http://hovehistory.blogspot.com/2015/04/st-anns-well-gardens-hove.html

National Media Museum. (2022). Beale's Choreutoscope, c 1890. Retrieved from Bridgeman Images: https://www.bridgemanimages.com/en/noartistknown/beale-s-choreutoscope-c-1890/object/asset/5062336

Nobel Prize Outreach. (2022). Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen – Biographical. Retrieved from NobelPrize.org: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1901/rontgen/biographical/

Rajadhyaksha, A. (1986). Neo-Traditionalism: Film as Popular Art in India. Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, 20-67.

Robinson, D. (2002). Funny Ladies: The Comediennes of the Silent Screen. Retrieved from La Cineteca del Friuili: http://www.cinetecadelfriuli.org/gcm/ed_precedenti/edizione2002/Funny_Ladies.html#introduction.html

Rutgers. (2022). Maguire & Baucus. Retrieved from Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences: https://edison.rutgers.edu/life-of-edison/companies/company-details/motion-pictures/maguire-baucus

Secord, J. A. (2002). Quick and Magical Shaper of Science. Science, 1648-1649.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2022). Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen. Retrieved from Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Wilhelm-Rontgen

The Kodak Collection at the National Media Museum, Bradford. (2022). Williamson 35mm cine camera. Retrieved from Science Museum Group: https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8209464/williamson-35mm-cine-camera-cine-camera

The Regency Society. (2022). Ivy Lodge. Retrieved from The James Gray Collection: http://regencysociety-jamesgray.com/volume12/source/jg_12_188.html

The Royal Household. (2022). Coronation. Retrieved from Official Website of the Royal Family: https://www.royal.uk/coronation

コメント